How to be an effective stockman with low-stress animal handling

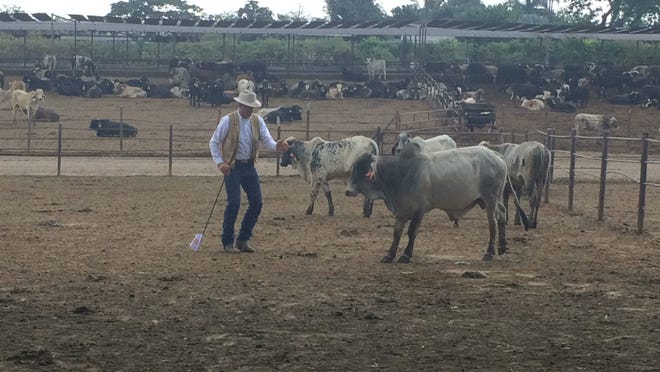

Wondering what more you could be doing to keep your relationship with your livestock thriving? Expert Curt Pate has some tips for you.

Pate is an internationally renowned speaker on stockmanship and horsemanship, known for his clinical demonstrations of animal handling. During a webinar sponsored by West Bend company GrassWorks, Pate said it's crucial for owners of farm animals like cattle, hogs, horses and sheep to apply the right amount of pressure while also maintaining trust with your animals.

Pate said the first thing to do is consider what's going on inside the animal's head. Their mind will focus on one thing at a time, rather than multitask, so remember that they can't graze and run at the same time. He added that putting too much stress on animals will wear down their immune system over time, as well as prevent them from taking full advantage of their nutrition and diet, and will lower their trust in you.

"They're going to get so stressed that they're going to shut their immune system down, because if you're going to run from a mountain lion or a wolf, there's no use fighting off a cold or the flu," Pate said. "Your veins and your arteries open up so you can run for a long ways, and that is when our cows get sick and don't do as well. "

Approaching an animal in the wrong way or at the wrong angle can trigger the "flight zone," Pate said – the snap reaction moment and switch to survival mode that will cause some to hightail it out of there, while causing others to become aggravated.

Be careful that you're also keeping animals on the "thinking" side of the brain rather than the "surviving" side, Pate said. The thinking side of the brain is their neutral state where the fight or flight instinct is not triggered.

Types of pressure

Pate said there's two main types of pressure: driving, where you're behind the animal driving them forward, and drawing, where you're in front of the animal drawing them forward. He also said maintaining pressure consists of trust in your relationship with your animals as well as keeping them engaged with constant movement.

Consider how different animals' eyes work. Hogs are the least able to see what's coming up behind them because their eyes are front-facing, whereas cows, horses and sheep have side-facing eyes that have a wider field of vision from front to back. Regardless, don't stray too far, because they don't have sharp eyesight that will allow them to recognize you from a far distance, Pate said.

"If you approach them from behind, they can't see as well, and if they're a flighty animal or afraid or aren't used to you, then you might have some (animals) going from thinking to surviving," Pate said. "So the eye is very important."

Pate said it's also important to compromise with your animals and meet them where they are. Their comfort is key to their health, productivity and trust, and to gain the upper hand you need to let them be comfortable. Pate recommends working with animals from the side, rather than the back, because it encourages comfort while also putting on enough pressure to get them to move where you want.

With cattle, Pate says you could try moving back and forth behind them at a flat angle rather than a steep angle. Come far enough to where they can see you if they turn their head a little, then as soon as they see you on one side head to the other, then rinse and repeat until you've driven them to where you need them.

It'll take some trial and error to figure out the right distance, he added, but once the pattern is established it'll be easier to get the animals heading in a straight line. Herding dogs can also accomplish this if trained.

"If you've ever watched a border collie dog or a gathering-type dog, they move back and forth, they go from one side to the other side. What they're doing is switching eyes – left eye, right eye – but they're also switching sides of the brain," Pate said. "It causes them to want to move forward far enough so they can get out of that range and try to get you on one side or the other."

However, drawing pressure also has its benefits and it can be done without the incentive of feed. Pate said that when you go up the side of an animal, they'll typically slow down or stop so they can turn to look at you with both eyes rather than just the one, which slows things down and becomes a distraction. Instead, try going back and forth in front of them or to the side so that they are forced to keep turning to look at you in different directions that average out in a straight line, Pate said.

Pate said it's important to use all three types of pressure to be an effective livestock handler, since many people only use one type of pressure. He also said that while herding dogs can be controversial, he highly recommends using them as tools on the farm as long as they're not overly aggressive in putting pressure on the animals.

"We don't want a real, aggressive tough dog. We don't want them biting and scaring the animal and tearing them up," Pate said. "We try to have a nice, soft dog that uses the right kind of pressure that we can maintain a relationship with our animals. So every time we come to the pasture and they see a dog with us, they don't try to run through the fence."

When you have animals in a paddock, Pate said you need to form a grazing rotation system where paddocks are fenced off from each other. For instance, if you have four paddocks in a row and you want to move them from the first to the second paddock, Pate recommended driving or drawing them out of the first paddock, moving them all the way down the "lane" in front of the paddocks and then moving them back up the lane to the second paddock.

Also consider creating a corral system that has tight spaces, Pate said, so that the animals get more accustomed to pressure put on them so they will move the way you want them to when they aren't restrained.

Balanc

Another component of livestock handling is knowing where the "balance point" is. Most sources say that point is at the shoulder for wide-angle eyes; if you go behind the balance point, the animal will go forward, and if you go in front of the balance point, they'll stop or turn. But Pate said that's not entirely accurate because the balance point is always changing.

"What's so important learning is where is that balance point," Pate said. "When I bring these cattle out of this paddock ... what I'm going to try to do is start moving that balance point farther forward. If you can move the balance point from the shoulder clear to the nose or 10 feet out in front of the nose, now you have control."

Pate said that even though taking this approach takes extra work, it's worth it because it'll also increase your profits with happier animals and better productivity. He also just enjoys driving his cattle because he wants to put the work into them with getting them plenty of exercise and keeping them engaged and interested.

"If you enjoy and like it, then you'll start looking for reasons to work livestock. My cattle get worked way more than anybody else's because I like it so much and I just want to do it more and more, I just can't get enough of it," Pate said. "The profit is in the making the profit ... you start enjoying what you're doing."