'Sidelined' in the midst of pandemic: Student nurses, doctors prepare amid COVID-19

Sarah Razner

Sarah Razner

Editor's note: College students studying to become teachers and nurses are expected to spend the last few months of their education gaining real life experience, but the pandemic caused significant ripples in schools and hospitals. This two-part series looks at how those students and their schools rose to the occasion, to keep their futures on track.

FOND DU LAC – As Erika Priewe returned to college in January, she had much to look forward to. A nursing student at Marian University, it was her final semester before graduation, and she was set to round out her education with a placement at Froedtert Hospital’s neuro intensive care unit. There, she would “take on a more independent role” and learn many skills, she said.

She couldn’t anticipate that within a couple months, health care partners would pull her and other nursing students from their placements as they sought to handle the coronavirus pandemic.

Around Wisconsin, students in nursing and teaching had their final semesters of schooling disrupted, leaving them and their teachers to adapt, and determine how COVID-19 would impact their future career plans.

Adapting to 'rapidly changing situations'

Throughout their workdays, nurses must respond “to rapidly changing situations” while providing “high-quality health care,” University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee College of Nursing Academic Affairs Coordinator Chris Peters said. This prepares them to adapt in serving patients and educating students — even in circumstances which they've never before encountered. No matter which specialty they are in, the “bedrock principle” is infection control, he said.

So, when news of the coronavirus and its impact began to emerge, nurses — including those in education — began to prepare.

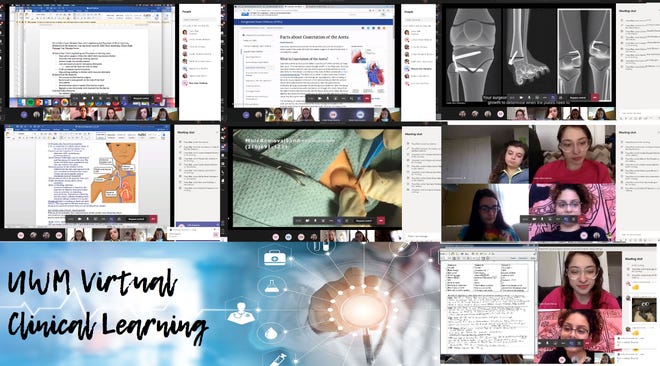

Faculty at Wisconsin’s largest nursing program, UW-Milwaukee, started making plans weeks before schools shut down, looking at impacted universities around the globe to create a road map. already encountering the virus as a guide.

First, UW-Milwaukee developed a way to screen students for the virus. Then, they shared that information with other nursing schools.

In March, the closures came.

As the coronavirus began to impact the state, colleges and universities shut down on-site classes and moved online.

At the same time, health care facilities closed off access to students — including medical students in their final semester. Due to a lack of personal protective equipment and legal liability, student doctors were removed from their clinical work, Medical College of Wisconsin-Central Wisconsin Dean Dr. Lisa Grill Dodson said.

When Priewe received an email from Froedtert saying they were suspending placements to limit how many people came into the hospital, it was “kind of heartbreaking,” she said.

During her preceptorship, which paired her one-on-one with a nurse, she felt she gained more knowledge and skill than at any other placement. Although she understood the need for safety, she felt "sidelined" from doing what she loved most: helping others.

Priewe still needed 30 hours to complete her preceptorship requirement. Now, the question became how?

At Marian University, Priewe and her classmates were able to stay in their preceptorships until spring mid-terms, meaning the coronavirus only impacted half of their final semester — a fraction of their four year education, which had already included numerous clinical and skill-building experiences, Associate Dean and Chief Nurse Administrator Kimberly A. Udlis said.

Faculty created a continuing of operation plan, listing each student, the clinical location and the number of hours and competencies remaining. With the information compiled, faculty began to integrate simulations and virtual options.

Although they are not the same as in-person clinical experiences where students work with real patients, the simulations provide a way to work on decision making and critical thinking skills, as well as support the concepts they needed to address, Udlis said.

Studies have shown that substituting humans for simulations does not make students less successful in meeting their course objectives, University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh College of Nursing Pre-Licensure Program Assistant Dean/Director Shelly Lancaster said, where students too moved to simulations to fulfill their requirements, even for their most immersive experience.

To make the simulation switch, schools needed to receive approval from the state’s program regulators.

A couple years before, the Wisconsin State Board of Nursing regulated that universities and colleges could not substitute more than 50% of clinical with simulations, Lancaster said. However, in the wake of the pandemic, Evers and the board lifted the 50% requirement, and in Evers’ Emergency Order 16, they left it to schools to meet the course objectives to graduate.

Priewe had to do 20 hours of simulations and a supplemental case study to fill the gap. The simulations she gave her “four or five patient scenarios,” and ask her to answer multiple choice questions, which included prioritizing patients, correctly administering medicine, and demonstrating skills they would use in health care settings, like dealing with upset patients, she said.

While they tested her, she missed the interaction with real patients and “therapeutic communication,” she said.

In some cases, medical simulations used real people.

Although medical students have completed their core curriculum by their final semester, they still need to complete electives, as well as an objective structured clinical exam, Dodson said. The exam requires students to engage with a “standardized patient,” as well as actors playing the roles of family members and medical staff.

The actors, as well as attending physicians, nurses and peers assess the students, and after, faculty meet with them individually to discuss what areas they need to focus on, Dodson said.

Typically, the exam takes place face-to-face, but this year, the Medical College of Wisconsin – Central Wisconsin worked with New York University and Texas Tech to put together a virtual exam. Across three time zones, instructors evaluated students as they interacted with actors online. The success of the exam proved to Dodson that “we can do it when we need to and maintain a lot of rigor and maintain standards even if the students aren’t physically there.”

Every aspect of life impacted by pandemic

As Priewe and her classmates scribbled out and rearranged their planners, they also had to balance other aspects of life affected by COVID-19. A resident care assistant at a long-term care facility, Priewe is doing as much school work and picking up as many work hours as she can.

In the facility, she engages with the pandemic on a level outside of schooling, as each time she comes into the facility, which is “pretty locked down” and not allowing visitors, she must be screened.

Priewe is not alone. Higher education faculty understand it was not just the challenge of online learning students had to face, but many others. Some students had to leave dorms and apartments to move back home. Others had to help care for younger siblings, have been called to work in medical care facilities, or work full-time to make ends meet, while dealing with the stress of a family member possibly being without work. Some students aligned with the Wisconsin National Guard have also been called to serve during this time, Lancaster said.

Due to this, schools are reminding students of mental health resources by sharing information about counselors, and putting a focus on self-care. At the Milwaukee School of Engineering, faculty’s first goal was to make sure students were in the “correct mindset” and felt comfortable with the switches MSOE School of Nursing Chair Dr. Carol Sabel said. To help them cope, students reviewed what they’ve done so far in their schooling to see the growth they’ve made and all they’ve accomplished

Schools have also pushed back important testing dates and professors send out frequent emails. Lectures are offered in variety of ways on, taking place live during the course’s typical time, but also recorded in case someone cannot attend or loses internet access. Priewe’s courses use PowerPoints with voice overs which can be paused and re-watched, and a Zoom session at a later time to ask questions — if they haven’t already forgotten them, Priewe said.

Still, she has tried to find a positive.

“It’s a great learning experience because nurses have to be able to re-prioritize and be flexible,” she said.

Coronavirus impact continues past graduation

Nursing students not only fear the impact COVID-19 has to their education, but their job prospects. Earlier this year, Priewe accepted a position as part of UW Health’s nurse residency program. During the interview process, she looked forward to taking a tour to get a “feel for the overall environment of the hospital,” but, due to the coronavirus, this wasn’t possible and they had to move the second interview online.

She felt confident in her choice and celebrated her new job. However, she and other student nurses have another hurdle to clear in their career past graduation. Nurses must take the National Council Licensure Examination, or NCLEX, to receive their nursing licenses.

Typically, they must pass the test within three months of receiving their temporary license. But as testing has become “very limited” during the pandemic due to sites closing, students have struggled to get a date. One student who graduated in February from MSOE has had her test canceled twice, Sabel said.

Educators like UW-Milwaukee’s Chris Peters lobbied state senators to have the Department of Health Services adjust the requirements, and got the deadline extended to six months. Schools, like MSOE, hoped to hold a “refresher course” once the safer at home order lifts to allow students to prepare.

Still, Priewe is uneasy. Statistics show that is better for students to take the exam within the first month of graduation, she said, and with testing delayed, she worries some students may be disadvantaged.

Medical students’ fate also waits on testing — at least for those in the middle of their education.

The issue the Medical College of Wisconsin is spending the most time on currently is figuring out how students will take their board exams. The exams are taken in four parts, and scores are needed to get into residency programs and get a license. While students typically take the exams in April, May and June, testing centers are closed and dates canceled.

If another wave of the virus occurs, education and all regulators will have to make adjustments, from state boards to accrediting bodies and health care facilities, Dodson said.

COVID-19 'defining moment' for generation

For medical students graduating this semester, they will begin their residencies more adaptable and possibly more understanding of “the human condition” than they would have with the “standard curriculum,” Medical College of Wisconsin's Dodson said.

“There’s a lot of trust you can put in someone who has gone through this and come out the other side,” she said.

When Priewe starts her position at UW Health, she’s confident she’ll “get the appropriate orientation," and said the important thing to remember is to maintain a focus on patient safety and if a nurse is unsure of what to do, they should ask for help.

“I will always have someone to lean on and I always have another nurse to ask,” she said.

Some students may not be as lucky as Priewe. Even in “optimal settings,” the first year out of school is “really difficult” for nursing students, UW-Oshkosh's Lancaster said.

Schools don’t know what the next six months to a year may look like for their graduates. New nurses are typically aren’t put into extreme situations “where 50 people are coding." Now, graduates may face the extreme, and whether that will cause nurses to burn out faster or decide to leave the job, Lancaster does not know.

Some students set to graduate in December have already expressed concerns to her of entering nursing, and how it will impact their families

“We talk about being selfless and nurses are altruistic, but at the end of the day no one wants to go to work and catch COVID and die,” Lancaster said.

Despite fears, many are still answering the call. In several nursing Facebook pages, Udlis has seen conversations about if the pandemic will make fewer people want to go into the field, but the “overwhelming” response was “no.” At UW-Milwaukee, the incoming nursing class has a waitlist.

“The current health crisis has not diminished the need for nurses and has not diminished students’ interest in becoming nurses,” Peters said, later adding: “They say that there are some events that define a generation and I think this going to be the event that defines this generation of new nurses. You’re going to come through this and say, ‘if I can respond to COVID-19, I can respond to anything.’"

RELATED:Pandemic doesn't have to be 'hopeless': Fond du Lac groups talk mental health amid COVID-19

RELATED:Fond du Lac County schools get creative with graduation plans amid school shut down

RELATED:Fond du Lac teachers parade in cars to see students during shutdown